|

Wrington Vale Patient-Practice Partnership Patient Records on-line Thursday, 6th September, 2007 |

|

Wrington Vale Patient-Practice Partnership Patient Records on-line Thursday, 6th September, 2007 |

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

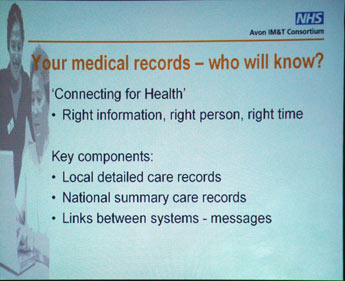

| The Wrington Vale Medical Practice PATIENT-PRACTICE PARTNERSHIP open meeting held at Churchill Primary School. Many of the issues raised by this major NHS scheme were addressed by Josie Tarnowski, Practice Manager, Adam Tuckett of the Avon Information Management & Technology Consortium (part of the local NHS), and Dr Charles Tricks of the Practice. |

|||||||

| Jose Tarnowski in her brief introduction struck at the heart of the matter. In a medical emergency, anywhere, would you want the doctor treating you, maybe trying to save your life, to have immediate access to information directly relevant to your condition, or would you prefer her to work by guesswork ? As with all complex issues, boiling them down to a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ reeks of over-simplification. However, precisely because of all the ifs, ands, and buts raised by our 3 speakers, and discussed by a highly attentive audience, it was clear that, unless the simple question is answered ‘yes’, there’s hardly any point in worrying about the whole range of attendant problems. The speakers used a graphic set of Powerpoint slides to help the audience keep up with the practicalities, the possibilities, the ethics, the politics, and the costs of an enterprise whose ultimate goal is to ensure that medical practitioners are not hindered in giving the best possible treatment to patients by lack of access to clinical information about them. Adam Tuckett described the process as being about linking all the disparate information systems currently in use or planned, into a single, coherent whole. As with any information system, there are concerns about security, access, fraud, manipulation, loss, and theft, but he pointed out this holds true for the present paper-based systems. This reminds us that we’re not moving from a near-perfect system into the unknown, but from an imperfect system into the partially known. And it is what we do know about the present state of IT, especially where it involves the internet, which should put us all on our guard. Who should ultimately manage and control such an information system – government, IT experts, NHS managers ? Could one envisage a situation, for example, notwithstanding all the safeguards of the Data Protection Act, of a high risk of extreme terrorist attack, in which the government might not regard it as for the greater good to allow police access to patients’ files ? Adam Tuckett was sanguine, at least at the local level at which he works, about the robustness of procedures to implement a ‘need-to-know’ principle of access to patient clinical information. Charles Tricks was equally reassuring in demonstrating his informed enthusiasm for the proven clinical benefits which are in prospect, matched with a healthy scepticism about the necessity or value of removing GPs with their unparalleled practical experience, from the core of the planning and design of systems whose sole purpose is to enable and support clinical excellence. He summed up with his personal answer to Josie’s original simple question (“Well, on balance, I suppose, yes”) although it clearly carries with it the absolute imperative for all concerned with developing the system, that it must be done in genuine consultation with patients, and under the direction of medical practitioners – not government, and especially not those who stand to make the inevitable billions from the cost of the project. It was noticeable many of his hearers were unaware – and unnerved – that the present Out-of-Hours arrangements provide no access at all to patient notes, a woeful state of affairs most likely to be seen as good a ground as any for the implementation of the central database. |

|||||||