|

Wrington at War 1939-45 by Mark Bullen |

|

Wrington at War 1939-45 by Mark Bullen |

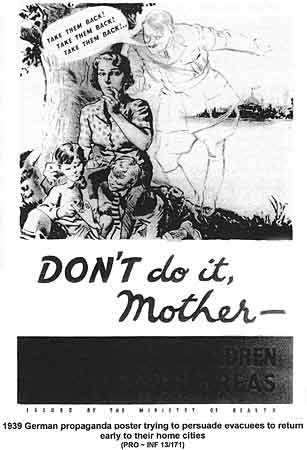

| Evacuees Whilst neither Wrington nor any of the other nearby villages were being bombed, much of the country saw, during the very first days of the war, a very different, but very real kind of invasion – by many thousands of evacuated school children and their mothers. The first evacuation began on 1 September 1939, as soon as it became obvious that war with Germany was unavoidable. Like many other things, this had been the subject of meticulous planning during the previous few months. Whilst parents had the choice of whether to send their children away or not, the duty of providing temporary homes in the target reception areas was a compulsory one. A few bare statistics will help to put the operation in perspective. Seventy-two London transport stations were involved. In four days the main-line railway companies carried more than 1,300,000 official evacuees in nearly 4,000 special trains. All over the country children and their wards arrived at the safe places by the bus and trainload. In Wrington, the Parish Council had nominated Mr. I.G. Gunning and Mrs. C.G. Biggs as their representatives in the local welfare committee of the government evacuation scheme “for the supervision of communal feeding, recreation and general welfare of evacuees”. The local paper reported that the Parish, which included Redhill and Downside, was initially scheduled to receive 190 women with children under five years of age and that the committee were experiencing difficulty in completing the arrangements to receive them. Evacuees were certainly in place within a month, because the Parish Magazine carried a brief article in its October edition: & On behalf of the whole parish of Wrington, I should like to extend a hearty welcome to all those who have had to leave their homes in London and have come to take up their abode with us. We realise what a wrench it must be to them so suddenly to have to leave their homes and we do want to make them feel at home here. On the other hand they will readily understand that it means a certain amount of upset in the village homes as well, and we are sure that allowances will be made on both sides. The Methodist Chapel has very kindly placed their schoolroom at the disposal of the visitors as a writing and reading room, and the Memorial Hall is open to them on Monday, Wednesday and Saturday afternoons.” Mrs. Diana Anson of West Hay, head of the local W.R.V.S. service, was put in practical charge of organizing the various billeting officers. One of their duties was to visit all the houses in the village to ascertain what room people had for accommodating evacuated children and their mothers. This caused considerable anxiety for some householders, who were understandably reluctant to open their homes to strange Londoners, particularly as they had no idea how long they were likely to stay. There was also resentment that some people, especially those who were better off, refused to accept evacuees and seemed to get away with it. As one person put it, “They would come round and ask you how many bedrooms you were using yet they’d go to the big houses which might have only one person living in them, and they didn’t make them have any.” That notwithstanding, Mrs. Anson reported in October that they had not yet been forced to use their compulsory powers, there being sufficient willing volunteers for the relatively small number of arrivals. Not everyone was reluctant. Olive Mellett (née Millard) explained to me how keen she was to do her bit and take in a couple of boys. “ In 1940, when the evacuees came, I said I wanted two boys. Well, the person who was in charge of evacuating, Gwen Organ, came along with two girls of about ten and eleven. I said, “I’ve already got two boys here.” These children had been on their way from Kilburn from 9 o’clock in the morning and this was 9 o’clock at night. The whole lot had been brought down to Axbridge and then as many as Wrington was going to take, were bussed to Wrington in the hall. Rene Kirk used to deal with the Guides and the Guides were there to help bring the children out to the families where they were going. Rene said she knew we wanted two boys so she sent these two boys over to me, Barry and Gordon. Barry’s mother had put his age on so that he would come – he was 4 in the February and came in the June. Gordon was five. She brought these two little kids – lovely – just what I wanted, that’s fine. Took them in and we were giving them supper when Miss Organ came with these two girls. So I said “But I’ve already got two boys.” She said, “Oh, no, you can’t have, because I didn’t think a young person like you, not married or anything, with your mother and father to look after should have two little boys.” So I said, “Well, I’ve got these boys here and I’m getting them ready for bed and they are staying.” So, at a stroke, Olive had obtained an extended family and has never looked back ! Well, she didn’t know what to do so this little girl looked up at me and said, “Don’t send us away, please.” I shall never forget it. I told them they could stay the night. We had a double bed in the back room. I remember pushing the girls in one bed and the boys in another. The next day she tried to persuade me to keep the girls but I told her that the boys were staying with me. I think I wanted boys because when I was young there were twin boys across the road and I used to play with them. Finally, in a mood of reckless desperation, we undertook to evolve a complete home for five people out of an empty cottage in the 1½ hours of daylight which then remained. It says much for the indomitable spirit of the British race that this was done". |

||||

|

||||

| Most children were evacuated without their parents. In these circumstances, many parents visited their children as often as they could: “ The parents of one of my evacuees are here for the weekend. They are much easier to deal with than the other family, who are inclined to get upstage and suffer from hurt feelings and grandiose flights of fancy with which I find it difficult to keep pace. Last week, after many attempts to come to some sort of an understanding about the children’s clothes, I dared to send a bill for shoe-mending to the father. This produced three pages of abuse from the young son, evidently the scholar and scribe of the household. |

||||